When it comes to physical performance, we know that there are differences between men and women (due to differences in hormones and neuromuscular efficiency).

But over the years, I’ve read and also heard that there’s a wider discrepancy between upper and lower body strength in women than in men.

From my experience coaching, I’ve also suspected this phenomenon. My hypothesis is that men generally have bigger upper bodies, wider shoulders and carry more upper body muscle mass than women, which in turn allows them to be stronger on upper body lifts.

Are women’s upper bodies not as strong in comparison to their lower bodies as compared to men? To be honest, I’m not 100% sure. Is there really a difference between the upper and lower body strength of men and women? Let’s find out.

Let’s look at the world records

To compare upper to lower body strength, we can compare the upper body lifts (using the press or bench press as a proxy for upper body strength) against the lower body lifts (using the deadlift and squat as a proxy for lower body strength).

For example, a man competing in a strengthlifting meet squats 100 kg, presses 50 kg and deadlifts 100 kg. We can infer that:

Upper body strength (using the press as a proxy) – 50 kg

Lower body strength (total for squat and deadlift as a proxy) – 200 kg

Hence the ratio of upper body strength:lower body strength – 0.25

We’ll use the data from world records in powerlifting and strengthlifting to find the heaviest weight lifted for each sport, gender, weight class, and age division. We then compare the upper and lower body strength of each data point to get the ratio of Upper:Lower. We then plot a graph to compare these ratios between the genders.

Some caveats:

- Because the lifter varies across the records for each lift, it’s not an accurate representation of each individual’s upper versus lower body strength. But it does accurately measure the strength of each weight class’ record holders, and there are enough data points for a solid statistical trend.

- There are two different upper body lifts used by different sports: powerlifting uses the bench press, and strengthlifting uses the press. So we will compare the lifts separately, i.e. bench vs squat and deadlift, and press vs squat and deadlift.

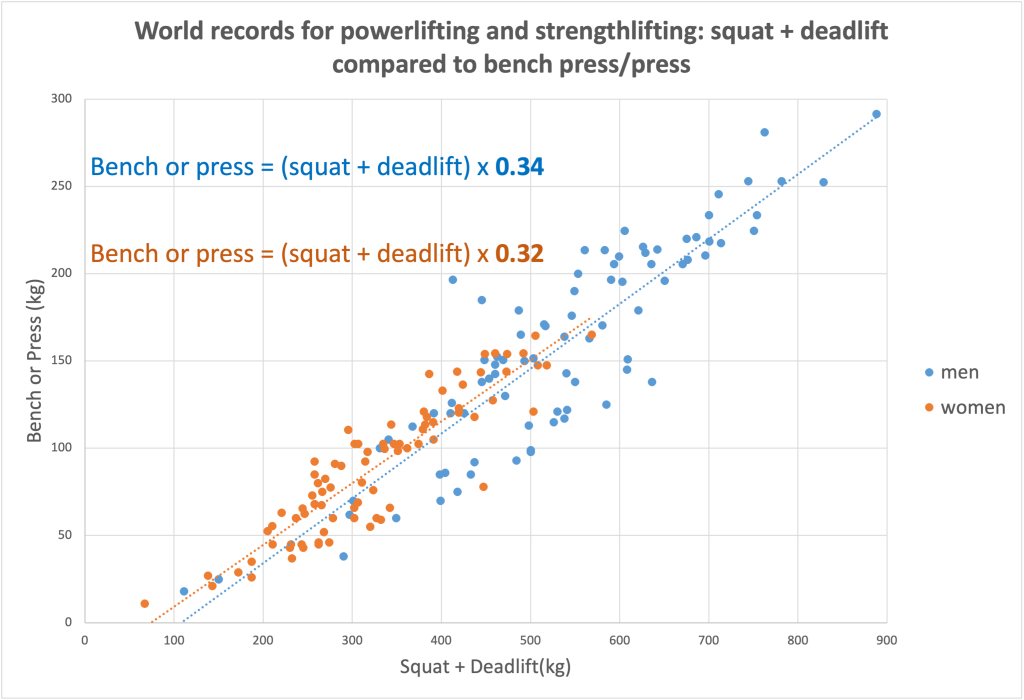

Here is the combined Upper:Lower ratio for the current powerlifting and strengthlifting world records:

The x-axis shows the lower body lifts, and the y-axis the upper body lifts. To get a statistically average ratio, what we want to look at is the gradient (y/x) of each trendline.

For men, the gradient is 0.34, which means that for every 1 kg on his squat and deadlift, he can lift 0.34 kg on his bench press/press.

For women, the gradient is 0.32, which means that for every 1 kg on her squat and deadlift, she can lift 0.32 kg on her bench press/press.

So there is a discrepancy between upper and lower body strength by gender – there is a 5.88% difference between upper body and lower body strength in women than in men.

(Graphing notes: we have fitted a linear trendline through the data points, with equation y = bx + c. The trendlines fit the points quite well, showing a significant statistical correlation between the Upper and Lower values. However, we’ve only kept the gradient (the ratio) because the rest of the equation is irrelevant.)

Is this true for both powerlifting and strengthlifting?

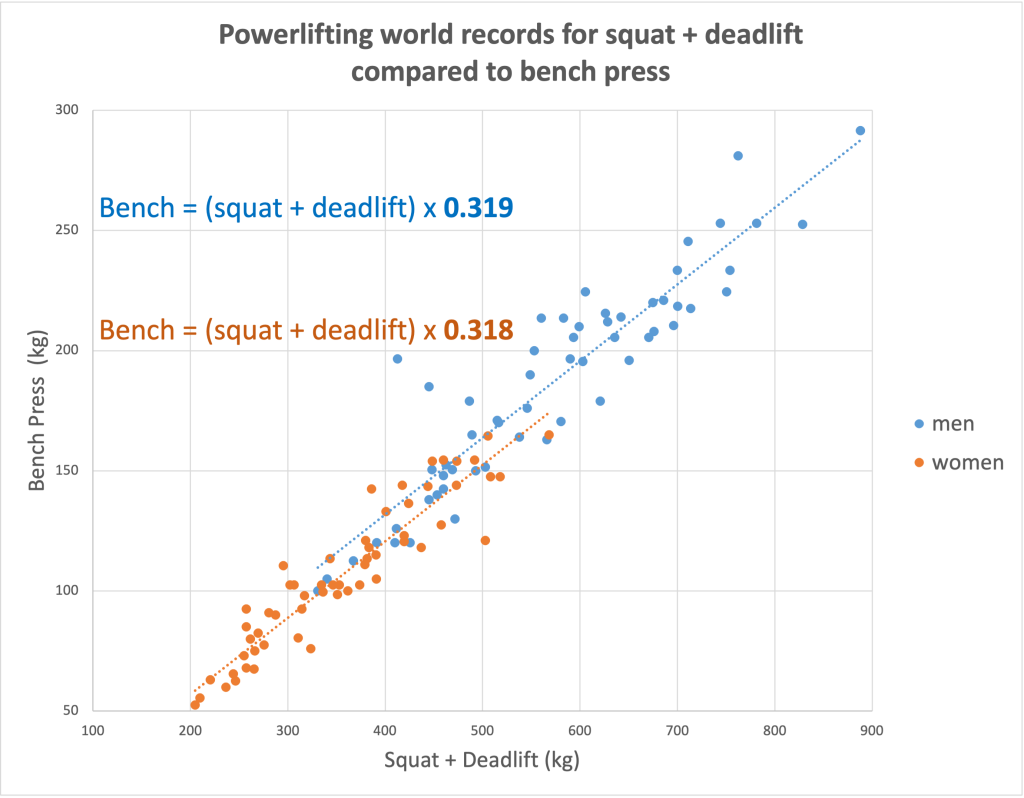

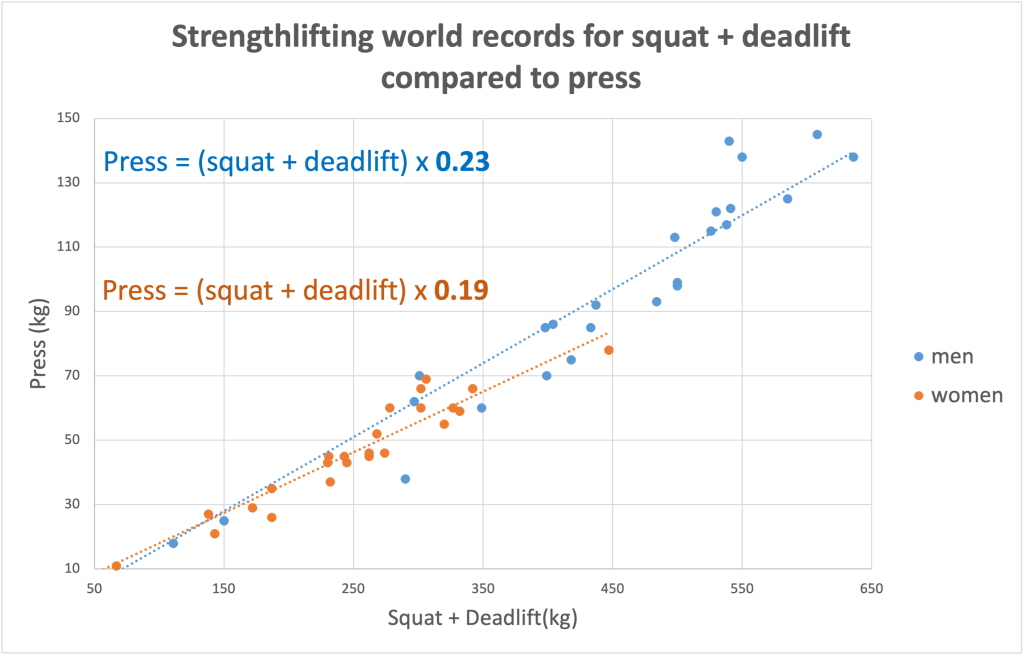

Powerlifting and strengthlifting are different sports, so let’s look at the data separately for a more granular interpretation.

For powerlifting, men have a Upper:Lower ratio of 0.319, and women have a ratio of 0.318. Men are still stronger than women in their upper body compared to their lower body, albeit just a slight bit – just 0.314% more.

For strengthlifting, men have a Upper:Lower ratio of 0.23, and women have a ratio of 0.19 – a difference of 21%. Now this is a more significant difference. In fact, this wider discrepancy in strengthlifting is probably a major contributor to the overall discrepancy in the combined chart above.

What causes the difference in Upper:Lower ratios for powerlifting and strengthlifting?

My hypothesis for the close gap between upper:lower ratios in powerlifting is that many lifters find ways within the rules to reduce the barbell’s range of motion (ROM) to put up heavier numbers on their lifts. On the bench press, this is achieved by having a wider grip and a big arch. Of course, you still need to be strong to lift heavy weights but this technique of reducing the distance the barbell has to travel allows them to lift more weight. From my observation, women are generally better at creating a big arch due to their overall better flexibility.

Additionally, having the same maximum grip width for all lifters, from the women’s U43 sub juniors to the men’s 120 open, means women lifters can potentially use a “wider” grip width in relation to their shoulder width. Bigger arch + “wider” grip = potentially more weight lifted.

Since the 1st of January 2023, the International Powerlifting Federation introduced some rules to address the issue of ridiculously short ROMs on the bench press that some lifters utilise. The introduction of the new rules did help but still leaves a lot to be desired. But I digress.

While the endeavour of reducing the barbell’s ROM may also be true on the deadlift, whereby lifters utilise the sumo deadlift to shorten their legs in the sagittal plane, is it only one part of our lower body strength calculation. We’ve still got the squat, a lift that powerlifters generally don’t try to reduce the range of motion.

This might explain the smaller Upper:Lower discrepancy in powerlifting compared to strengthlifting. Between the two sports, I’d argue that strengthlifting is a better gauge of the discrepancy, because the rules don’t allow the lifter to reduce the barbell’s ROM in an effort to lift more weight.

Our hypothesis looks correct, but why?

Our hypothesis is that men have wider shoulders and more upper body lean mass, which leads to increased upper body strength.

So far, our data supports this. But is the reason only biological?

From my observations, men generally prefer to train their upper bodies, and women generally prefer to train their lower bodies. Perhaps we’re driven by unconscious beauty standards, where men prefer wide shoulders and women a perkier derriere. Walk into any commercial gym and you’ll see the guys benching, bicep curling, shoulder pressing or doing chin ups, while the girls are doing hip thrusts, lunges, squats or some form of glute exercises. The chances are close to zero that you’ll see gyms targeting women to build big guns or ads getting men to join an abs, buns and thighs class.

On the lifts or body parts that we prefer, we’re likely to spend more time and effort training them, sometimes at the expense of ignoring the other lifts. This explains the number of guys walking around the gym with jacked and muscular upper bodies but with chicken legs.

What this means for your training

We’ve established that there is a discrepancy between the genders, based on the records for each weight class and event.

What can you do with these observations?

First, train and get your entire body strong, not just on the lifts or body parts that you like or are already good at. Being generally strong overall makes you a more physically useful person and has more carryover to your daily activities or sports.

There’s no point in having a huge bench or big pecs if you struggle to pick something heavy off the floor. Or having a strong squat with big glutes but straining to lift your luggage into the overhead compartment.

So while there’s a discrepancy between the genders, that’s just a phenomenon to note. It’s not an excuse to sandbag lifts that you’re not “as strong at”.

References:

Strengthlifting records https://dzn481so72a1d.cloudfront.net/records/

International Powerlifting Federation men’s world records https://goodlift.info/records.php?fd=0&ac=0&sx=M&eq=1

International Powerlifting Federation women’s world records https://goodlift.info/records.php?fd=0&ac=0&sx=W&eq=1